Urban life offers a different rhythm for our companion animals compared to their rural counterparts. While veterinary professionals are well-versed in the obvious welfare concerns, such as diet, vaccination, and parasite control, there is a growing need to consider the subtler, cumulative effects of an urban environment on the musculoskeletal, neurological, and overall functional health of dogs and, increasingly, cats. Understanding these environmental challenges is essential for effective prevention, treatment, and performance of long-term health care.

Unique Physical and Biomechanical Challenges in Urban Environments

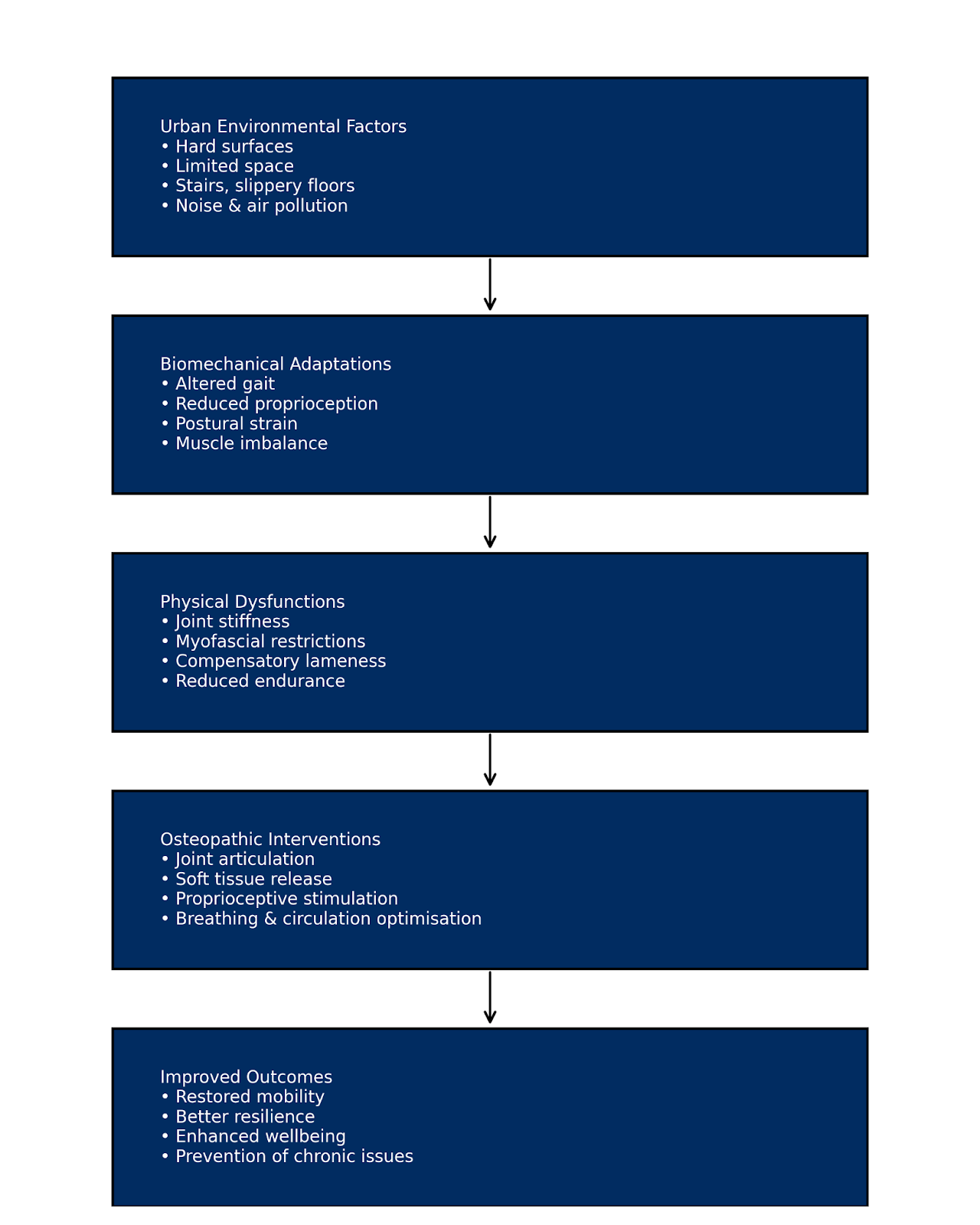

City living often restricts animals’ opportunities for natural, varied movement. Pavement walking on uniform, hard surfaces alters the normal biomechanics of gait, affecting shock absorption through the limbs and spine. Over time, repetitive high-impact loading can contribute to joint microtrauma, particularly in young, developing animals or seniors with age-related cartilage changes.

The physical environment also presents navigational and postural challenges. Stairs, escalators, slippery tiled floors, curbs, and sharp turns around obstacles require sudden accelerations, decelerations, and lateral movements that can strain soft tissues. For cats in high-rise apartments, reduced vertical territory or reliance on artificial climbing structures can alter normal kinetic chains, especially if those structures are poorly designed or unstable.

Confinement to small living spaces often results in under-stimulation of proprioception - the animal’s awareness of its body in space. Without varied terrain, micro-adjustments in posture and coordination are reduced, leading to subtle muscular imbalances and decreased joint stability. These patterns may remain unnoticed until compensatory strain manifests as stiffness, lameness, or behavioural changes.

Environmental Stressors and Their Somatic Impact

Urban noise pollution, unpredictable foot traffic, and the density of other dogs or people in walking routes can create sustained low-level stress. Chronic sympathetic nervous system activation can contribute to muscle hypertonicity, altered breathing mechanics, and reduced capacity for tissue repair. In some cases, this physiological stress blends with physical discomfort to influence behaviour, such as reactivity, reluctance to walk in certain areas, or avoidance behaviours.

Air quality also plays a role. Higher exposure to pollutants can subtly affect oxygenation and circulation, influencing tissue metabolism and recovery after exertion. In brachycephalic breeds, already prone to respiratory compromise, this adds a further biomechanical consequence as they adapt their posture and gait to optimise breathing.

The Role of Osteopathy in Addressing Urban-Related Issues

Osteopathic assessment and treatment offers a whole-body, functional approach ideally suited to these multifactorial challenges. Rather than focusing solely on symptomatic areas, osteopaths assess the integrated relationship between structure and function - how altered biomechanics in one region influence distant tissues through fascial, articular, and neurological connections.

For example, in a city dog presenting with forelimb stiffness, an osteopath may identify pelvic imbalance caused by years of repetitive stair use, or myofascial tension patterns developed from bracing against slippery indoor surfaces. Gentle articulation, soft tissue release, and techniques aimed at improving joint range of motion and proprioceptive input can restore more balanced movement patterns.

Osteopathy also helps improve resilience to environmental stressors. By optimising thoracic mobility, diaphragmatic function, and circulatory efficiency, treatment can support recovery from physical strain and enhance overall vitality. In cats, osteopathy may be used to address spinal rigidity from reduced climbing or to release tension in forequarters caused by abrupt, high-impact landings on hard floors.

Expanding Skills for Veterinary Professionals in the Urban Context

For veterinarians and veterinary nurses working in city practices, training in animal osteopathy offers a significant expansion of clinical tools. Many urban patients present with subtle, non-specific issues - mild stiffness, intermittent lameness, performance changes, or “off” behaviour - that may not correlate with radiographic or orthopaedic findings. Osteopathy provides a structured, evidence-informed method to assess and treat these functional disturbances before they progress to more serious pathology.

It also enhances client engagement. Urban pet owners often have high expectations for their animals’ health and well-being, and value proactive, non-invasive interventions. Offering osteopathy alongside conventional care supports preventive medicine, broadens treatment plans for chronic conditions, and positions the clinician as a provider of integrative, comprehensive healthcare.

Conclusion

Urban environments impose unique biomechanical and physiological demands on companion animals. Demands that may be invisible until they accumulate into dysfunction. Recognising these patterns and applying osteopathic principles to restore balance and optimise movement can transform long-term health outcomes. For veterinary professionals, human osteopaths, and other animal therapy providers in city practice, integrating osteopathy is not just an additional service; it is an evolution of skillset, allowing them to address the nuanced intersection of environment, structure, and function in their patients.

.png)

.png)